美 오바마2기 정부의 아시아 전략과 대북정책

<톰 도닐런 연설원문,중국 대변인 입장, 중 외교부장 발언등포함>

지해범(조선일보 동북아연구소장)

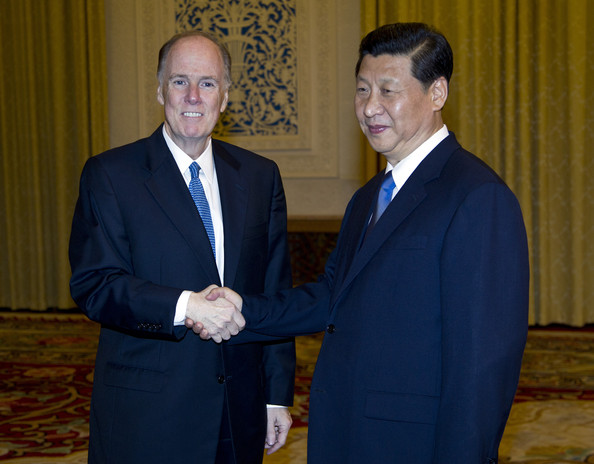

<톰 도닐런과 시진핑. 2012년 7월/출처=짐비오.com>

미국 오바마 2기 행정부의 아시아 외교전략과 대북정책이 실체를 드러냈다.

톰 도닐런 미 백악관 국가안보보좌관은 11일 뉴욕에서 열린 아시아 소사이어티 연설에서 아시아-태평양 재균형을 위한5대 전략을 밝혔다. [불법복제-전재금지]

1. 아태 지역 동맹(한국-일본-호주-태국-필리핀)의강화와 안보의 보장

2. 이머징 파워(인도-인도네시아-브루나이)와의 파트너십 심화 [불법복제-전재금지]

3. 중국과의 건설적 관계(constructive relationship) 구축을 위한 군사대화, 상호의존적 경제협력의 강화, 사이버 테러위협의 해소[기존의 강대국인 미국과 부상하는 강대국인 중국 사이에는 협력과 경쟁이 공존. 오바마와 시진핑은 두 나라의 ‘새로운 관계 모델(new model of relations)’을 구축해야할책임이 있다/중국의 ‘新型大國關係’론에 상응하는 듯한 용어]

4. 아세안 등을 통한지역협력체제 구현

5. 지속번영을 위한 지역경제 지원 [불법복제-전재금지]

도닐런 보좌관은 또북한의 핵실험과 도발위협과 관련 "나쁜 행동에 보상은 없으며, 국제적 독자적 제재를 지속할 것"이라고 천명했다. 오바마 1기 정부의 대북정책인 ‘전략적 인내’가 북한의 나쁜행동을 방치하는 것이었다면, 2기 정부는 자체적으로, 그리고 국제사회와 함께 압박을 강화하겠다는 것이다. 도닐런이 밝힌 대북정책 4원칙은 다음과 같다. [불법복제-전재금지]

1. 한미일 삼각 협력의 강화와 미중간 협조를 통해 북한 도발 대응과 외교적 해결책을모색한다.

2. 북한의 나쁜 행동에 보상은 없다(미국은 같은 말을 두번 사지 않는다/We won’t buy the same horse twice). 북한이 노선을 바꾸지 않으면 북핵과 미사일개발을 저지하기 위한 국제적-국내적 제재를 강화한다. [불법복제-전재금지]

3. 북한의 핵미사일 위협으로부터 미국과 동맹국(한국-일본)을 보호하고, 북 핵확산을 차단한다.

4. 북한이 노선을 바꾸면 미국은 북한의 경제개발과 식량난 해결을 도울 준비가 돼있다. [불법복제-전재금지]

이상의 내용으로 볼 때, 오바마 2기 정부는보다 실질적이고 실리적으로’아시아 개입’ 정책을 추진할 것으로 예상된다. 특히아태지역에서 중국의 시진핑 정부와 협력하면서도이 지역에서 미국의영향력과 이익을 유지-확대하려고 노력할 것으로 보인다.이러한 오바미의 아시아 회귀정책에 대해 화춘잉 중국 외교부 대변인은 "환영한다"는 입장을 밝혔다./아래 자료 참조 [불법복제-전재금지]

대북정책과 관련하여 미국은중국과의 협조 위에서 대북압박을 강화할 것으로 예상된다.이에따라 북한 지도부의 생각과 행동이 바뀌지 않는 한, 한반도에서 대화 국면은기대하기 어려울 것 같다. 이런 상황에서 박근혜 정부는 대미-대중-대북전략의 면밀한 균형을 추구하면서주도적인 한반도외교를 펼쳐나갈 필요가 있겠다./hbjee@chosun.com [불법복제-전재금지]

<톰 도닐런/출처=뉴욕타임스>

<톰 도닐런 미국 백악관 국가안보보좌관 연설 전문/2013.3.11, 뉴욕, 아시아 소사이어티>

For Immediate Release

March 11, 2013

Remarks By Tom Donilon, National Security Advisory to the President: "The United States and the Asia-Pacific in 2013"

The Asia Society

New York, New York

Monday, March 11, 2013

“The United States and the Asia-Pacific in 2013”

As Prepared for Delivery –

Thank you, Henrietta, for that kind introduction and for your service, both in government and here at the Asia Society. And thank you, Suzanne, for bringing us together today. I am honored to be with you, especially in these beautiful surroundings. For almost sixty years, this organization has connected cultures— Asian and American—our ideas, leaders and people.

Of course, one of those people, a real presence here at the Asia Society, was your chairman and my friend of thirty years, Richard Holbrooke. Richard was famous for his work from the Balkans to South Asia. But he was also a real Asia hand as the youngest-ever Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia. Richard dedicated himself to the idea that progress and peace was possible—a lesson we carry forward, not only in Southwest Asia, where he worked so hard, but across the Asia-Pacific. I’ve come here today because this project has never been more consequential—the future of the United States has never been more closely linked to the economic, strategic and political order emerging in the Asia-Pacific.

Last November, I gave a speech in Washington outlining how the United States is rebalancing our global posture to reflect the growing importance of Asia. As President Obama’s second term begins, I want to focus on some of the specific challenges that lay ahead.

This is especially timely because this is a period of transition in Asia. New leaders have taken office in Tokyo and Seoul. In Beijing, China’s leadership transition will be completed this week. President Obama and those of us on his national security team have already had constructive conversations with each incoming leader. We’ll be seeing elections in Malaysia, Australia and elsewhere. These changes remind us of the importance of constant, persistent U.S. engagement in this dynamic region.

Why Rebalance Toward Asia

Let me begin by putting our rebalance to the Asia-Pacific in context. Every Administration faces the challenge of ensuring that cascading crises do not crowd out the development of long-term strategies to deal with transcendent challenges and opportunities.

After a decade defined by 9/11, two wars, and a financial crisis, President Obama took office determined to restore the foundation of the United States’ global leadership—our economic strength at home. Since then the United States has put in place a set of policies that have put our economy on the path to recovery, and helped create six million U.S. jobs in the last thirty-five months.

At the same time, renewing U.S. leadership has also meant focusing our efforts and resources not just on the challenges that make today’s headlines, but on the regions that will shape the global order in the decades ahead. That’s why, from the outset—even before the President took office—he directed those of us on his national security team to engage in a strategic assessment, a truly global examination of our presence and priorities. We asked what the U.S. footprint and face to the world was and what it ought to be. We set out to identify the key national security interests that we needed to pursue. We looked around the world and asked: where are we over-weighted? Where are we underweighted?

That assessment resulted in a set of key determinations. It was clear that there was an imbalance in the projection and focus of U.S. power. It was the President’s judgment that we were over-weighted in some areas and regions, including our military actions in the Middle East. At the same time, we were underweighted in other regions, such as the Asia-Pacific. Indeed, we believed this was our key geographic imbalance.

On one level, this reflected a recognition of the critical role that the United States has played in Asia for decades, providing the stabilizing foundation for the region’s unprecedented social and economic development. Beyond this, our guiding insight was that Asia’s future and the future of the United States are deeply and increasingly linked. Economically, Asia already accounts for more than one-quarter of global GDP. Over the next five years, nearly half of all growth outside the United States is expected to come from Asia. This growth is fueling powerful geopolitical forces that are reshaping the region: China’s ascent, Japan’s resilience, and the rise of a “Global Korea,” an eastward-looking India and Southeast Asian nations more interconnected and prosperous than ever before.

These changes are unfolding at a time when Asia’s economic, diplomatic and political rules of the road are still taking shape. The stakes for people on both sides of the Pacific are profound. And the U.S. rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific is also a response to the strong demand signal from leaders and publics across the region for U.S. leadership, economic engagement, sustained attention to regional institutions and defense of international rules and norms.

What Rebalancing Is, and What It Isn’t

Against this backdrop, President Obama has been clear about the future that the United States seeks. And I would encourage anyone who has not already done so to read the President’s address to the Australian parliament in Canberra in 2011. It is a definitive statement of U.S. policy in the region; a clarion call for freedom; and yet another example of how, when it comes to the Asia-Pacific, the United States is “all in.”

As the President explained in Canberra, the overarching objective of the United States in the region is to sustain a stable security environment and a regional order rooted in economic openness, peaceful resolution of disputes, and respect for universal rights and freedoms.

To pursue this vision, the United States is implementing a comprehensive, multidimensional strategy: strengthening alliances; deepening partnerships with emerging powers; building a stable, productive, and constructive relationship with China; empowering regional institutions; and helping to build a regional economic architecture that can sustain shared prosperity.

These are the pillars of the U.S. strategy, and rebalancing means devoting the time, effort and resources necessary to get each one right. Here’s what rebalancing does not mean. It doesn’t mean diminishing ties to important partners in any other region. It does not mean containing China or seeking to dictate terms to Asia. And it isn’t just a matter of our military presence. It is an effort that harnesses all elements of U.S. power—military, political, trade and investment, development and our values.

Perhaps most telling, this rebalance is reflected in the most valuable commodity in Washington: the President’s time. It says a great deal, for instance, that President Obama made the determination that the United States would participate every year in the East Asia Summit at the Head of State level and hold U.S.-ASEAN summits; that he has met bilaterally with nearly every leader in Southeast Asia, either in the region or in Washington; and that he has engaged with China at an unprecedented pace, including twelve face-to-face meetings with Hu Jintao.

Let me turn to each pillar of our strategy and several of the challenges we face in 2013.

Alliances

First, we will continue to strengthen our alliances. For all of the changes in Asia, this much is settled: our alliances in the region have been and will remain the foundation of our strategy. I feel confident is saying that our alliances are stronger today than ever before.

Our alliance with Japan remains a cornerstone of regional security and prosperity. I am not sure American-Japanese friendship has ever been more powerfully manifest than it was two years ago today, on 3/11, after the tsunami and Fukishima nuclear crisis. As allies and friends, Americans inside and outside government rushed to lend a hand to Japan’s disaster response and recovery.

That same spirit of solidarity was evident when Japan’s new Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, became one of the first foreign leaders President Obama hosted in his second term. They had excellent discussions on trade, expanding security cooperation, and the next steps toward realigning U.S. forces in Japan. Looking ahead, there is scarcely a regional or global challenge in the President’s second-term agenda where the United States does not look to Japan to play an important role.

With the Republic of Korea, the United States is building on our joint vision for a global alliance and deeper trading partnership. I just returned from Seoul, where I attended the inauguration of President Park, Korea’s first woman president. I was struck by how much our leaders have in common in terms of their priorities and vision. When we met, I conveyed to President Park President Obama’s unwavering commitment to the defense of the Republic of Korea, and President Park gave her full support to modernizing our alliance and continuing the effort to partner on a wide range of regional and global issues. During my visit, President Park accepted President Obama’s invitation to visit Washington, and I can announce today that we look forward to welcoming her to the White House in May.

In Japan and South Korea, the United States can look to new leaders who are firmly committed to close security cooperation with the United States. This is no accident and no surprise, because polls in both countries show public support for their alliance with the United States in the range of 80 percent. At the same time, it is clear that, as we look forward, maintaining security in a dynamic region will demand greater trilateral coordination from Japan, Korea and the United States.

With Australia—following the President’s visit and joint announcement with Prime Minister Gillard of the rotational deployment of U.S. Marines—we are bringing our militaries even closer. Prime Minister Gillard has been an outstanding partner in our efforts to advance prosperity and security to the Asia-Pacific region. The United States has reinvigorated longstanding alliances with Thailand and the Philippines to address counterterrorism, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Philippine President Aquino’s visit to Washington and President Obama’s visit to Thailand and meeting with Prime Minister Yingluck both speak to another key facet of our strategy—the United States is not only rebalancing to the Asia-Pacific, we are rebalancing within Asia to recognize the growing importance of Southeast Asia. Just as we found that the United States was underweighted in East Asia, we found that the United States was especially underweighted in Southeast Asia. And we are correcting that.

In these difficult fiscal times, I know that some have questioned whether this rebalance is sustainable. After a decade of war, it is only natural that the U.S. defense budget is being reduced. But make no mistake: President Obama has clearly stated that we will maintain our security presence and engagement in the Asia-Pacific. Specifically, our defense spending and programs will continue to support our key priorities – from our enduring presence on the Korean Peninsula to our strategic presence in the western Pacific.

This means that in the coming years a higher proportion of our military assets will be in the Pacific. Sixty percent of our naval fleet will be based in the Pacific by 2020. Our Air Force is also shifting its weight to the Pacific over the next five years. We are adding capacity from both the Army and the Marines. The Pentagon is working to prioritize the Pacific Command for our most modern capabilities – including submarines, Fifth-Generation Fighters such as F-22s and F-35s, and reconnaissance platforms. And we are working with allies to make rapid progress in expanding radar and missile defense systems to protect against the most immediate threat facing our allies and the entire region: the dangerous, destabilizing behavior of North Korea.

North Korea

Let me spend a few moments on North Korea.

For sixty years, the United States has been committed to ensuring peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula. This means deterring North Korean aggression and protecting our allies. And it means the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. The United States will not accept North Korea as a nuclear state; nor will we stand by while it seeks to develop a nuclear-armed missile that can target the United States. The international community has made clear that there will be consequences for North Korea’s flagrant violation of its international obligations, as the UN Security Council did again unanimously just last week in approving new sanctions in response to the North’s recent provocative nuclear test.

U.S. policy toward North Korea rests on four key principles:

First, close and expanded cooperation with Japan and South Korea. The unity that our three countries have forged in the face of North Korea’s provocations—unity reaffirmed by President Park and Prime Minister Abe —is as crucial to the search for a diplomatic solution as it is to deterrence. The days when North Korea could exploit any seams between our three governments are over.

And let me add that the prospects for a peaceful resolution also will require close U.S. coordination with China’s new government. We believe that no country, including China, should conduct “business as usual” with a North Korea that threatens its neighbors. China’s interest in stability on the Korean Peninsula argues for a clear path to ending North Korea’s nuclear program. We welcome China’s support at the UN Security Council and its continued insistence that North Korea completely, verifiably and irreversibly abandon its WMD and ballistic missile programs.

Second, the United States refuses to reward bad North Korean behavior. The United States will not play the game of accepting empty promises or yielding to threats. As former Secretary of Defense Bob Gates has said, we won’t buy the same horse twice. We have made clear our openness to authentic negotiations with North Korea. In return, however, we’ve only seen provocations and extreme rhetoric. To get the assistance it desperately needs and the respect it claims it wants, North Korea will have to change course. Otherwise, the United States will continue to work with allies and partners to tighten national and international sanctions to impede North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. Today, the Treasury Department is announcing the imposition of U.S. sanctions against the Foreign Trade Bank of North Korea, the country’s primary foreign exchange bank, for its role in supporting North Korea’s WMD program.

By now it is clear that the provocations, escalations and poor choices of North Korea’s leaders are not only making their country less secure – they are condemning their people to a level of poverty that stands in stark contrast not only to South Korea, but every other country in East Asia.

Third, we unequivocally reaffirm that the United States is committed to the defense of our homeland and our allies. Recently, North Korean officials have made some highly provocative statements. North Korea’s claims may be hyperbolic – but as to the policy of the United States, there should be no doubt: we will draw upon the full range of our capabilities to protect against, and to respond to, the threat posed to us and to our allies by North Korea. This includes not only any North Korean use of weapons of mass destruction—but also, as the President made clear, their transfer of nuclear weapons or nuclear materials to other states or non-state entities. Such actions would be considered a grave threat to the United States and our allies and we will hold North Korea fully accountable for the consequences.

Finally, the United States will continue to encourage North Korea to choose a better path. As he has said many times, President Obama came to office willing to offer his hand to those who would unclench their fists. The United States is prepared to help North Korea develop its economy and feed its people—but it must change its current course. The United States is prepared to sit down with North Korea to negotiate and to implement the commitments that they and the United States have made. We ask only that Pyongyang prove its seriousness by taking meaningful steps to show it will abide by its commitments, honor its words, and respect international law.

Anyone who doubts the President’s commitment needs look no further than Burma, where new leaders have begun a process of reform. President Obama’s historic visit to Rangoon is proof of our readiness to start transforming a relationship marked by hostility into one of greater cooperation. Burma has already received billions in debt forgiveness, large-scale development assistance, and an influx of new investment. While the work of reform is ongoing, Burma has already broken out of isolation and opened the door to a far better future for its people in partnership with its neighbors and with the United States. And, as President Obama said in his speech to the people of Burma, we will continue to stand with those who continue to support rights, democracy and reform. So I urge North Korea’s leaders to reflect on Burma’s experience.

Emerging Powers

Even as we keep our alliances strong to deal with challenges like North Korea, we continue to carry out a second pillar of our strategy for the Asia-Pacific: forging deeper partnerships with emerging powers.

To that end, the President considers U.S. relations with India—the world’s largest democracy—to be “one of the defining partnerships of the twenty-first century.” From Prime Minister Singh’s visit in 2009 to the President’s trip to India in 2010, the United States has made clear at every turn that we don’t just accept India’s rise, we fervently support it.

U.S. and Indian interests powerfully converge in the Asia-Pacific, where India has much to give and much to gain. Southeast Asia begins in Northeast India, and we welcome India’s efforts to “look East,” from supporting reforms in Burma to trilateral cooperation with Japan to promoting maritime security. In the past year, for example, India-ASEAN trade increased by 37 percent to $80 billion.

The United States has also worked hard to realize Indonesia’s potential as a global partner. We have put in place a wide-ranging Comprehensive Partnership. We have welcomed Indonesia’s vigorous participation in the region’s multilateral forums, including hosting APEC and promoting ASEAN unity. We are also working with Indonesia and Brunei on a major new initiative to mobilize capital to help bring clean and sustainable energy to the Asia-Pacific. And, of course, no U.S. President has ever had closer personal ties to an Asia-Pacific nation than President Obama does with Indonesia—a warm relationship that was on full display in November 2010 when the President visited Jakarta.

China

The third pillar of our strategy is building a constructive relationship with China. The President places great importance on this relationship because there are few diplomatic, economic or security challenges in the world that can be addressed without China at the table and without a broad, productive, and constructive relationship between our countries. And we have made substantial progress in building such a relationship over the past four years.

As China completes its leadership transition, the Administration is well positioned to build on our existing relationships with Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang and other top Chinese leaders. Taken together, China’s leadership transition and the President’s re-election mark a new phase in U.S.-China relations – with new opportunities.

Of course, the U.S.-China relationship has and will continue to have elements of both cooperation and competition. Our consistent policy has been to improve the quality and quantity of our cooperation; promote healthy economic competition; and manage disagreements to ensure that U.S. interests are protected and that universal rights and values are respected. As President Obama has made clear, the United States speaks up for universal values because history shows that nations that uphold the rights of their people are ultimately more successful, more prosperous and more stable.

As President Obama has said many times, the United States welcomes the rise of a peaceful, prosperous China. We do not want our relationship to become defined by rivalry and confrontation. And I disagree with the premise put forward by some historians and theorists that a rising power and an established power are somehow destined for conflict. There is nothing preordained about such an outcome. It is not a law of physics, but a series of choices by leaders that lead to great power confrontation. Others have called for containment. We reject that, too. A better outcome is possible. But it falls to both sides—the United States and China—to build a new model of relations between an existing power and an emerging one. Xi Jinping and President Obama have both endorsed this goal.

To build this new model, we must keep improving our channels of communication and demonstrate practical cooperation on issues that matter to both sides.

To that end, a deeper U.S.-China military-to-military dialogue is central to addressing many of the sources of insecurity and potential competition between us. This remains a necessary component of the new model we seek, and it is a critical deficiency in our current relationship. The Chinese military is modernizing its capabilities and expanding its presence in Asia, drawing our forces into closer contact and raising the risk that an accident or miscalculation could destabilize the broader relationship. We need open and reliable channels to address perceptions and tensions about our respective activities in the short-term and about our long-term presence and posture in the Western Pacific.

It is also critical that we strengthen the underpinnings of our extensive economic relationship, which is marked by increasing interdependence. We have been clear with Beijing that as China takes a seat at a growing number of international tables, it needs to assume responsibilities commensurate with its economic clout and national capabilities. As we engage with China’s new leaders, the United States will encourage them to move forward with the reforms outlined in the country’s twelfth Five Year Plan, including efforts to shift the country away from its dependence on exports toward a more balanced and sustainable consumer-oriented growth model. The United States will urge a further opening of the Chinese market and a leveling of the playing field. And the United States will seek to work together with China to promote international financial stability through the G-20 and to address global challenges such as climate change and energy security.

Another such issue is cyber-security, which has become a growing challenge to our economic relationship as well. Economies as large as the United States and China have a tremendous shared stake in ensuring that the Internet remains open, interoperable, secure, reliable, and stable. Both countries face risks when it comes to protecting personal data and communications, financial transactions, critical infrastructure, or the intellectual property and trade secrets that are so vital to innovation and economic growth.

It is in this last category that our concerns have moved to the forefront of our agenda. I am not talking about ordinary cybercrime or hacking. And, this is not solely a national security concern or a concern of the U.S. government. Increasingly, U.S. businesses are speaking out about their serious concerns about sophisticated, targeted theft of confidential business information and proprietary technologies through cyber intrusions emanating from China on an unprecedented scale. The international community cannot afford to tolerate such activity from any country. As the President said in the State of the Union, we will take action to protect our economy against cyber-threats.

From the President on down, this has become a key point of concern and discussion with China at all levels of our governments. And it will continue to be. The United States will do all it must to protect our national networks, critical infrastructure, and our valuable public and private sector property. But, specifically with respect to the issue of cyber-enabled theft, we seek three things from the Chinese side. First, we need a recognition of the urgency and scope of this problem and the risk it poses—to international trade, to the reputation of Chinese industry and to our overall relations. Second, Beijing should take serious steps to investigate and put a stop to these activities. Finally, we need China to engage with us in a constructive direct dialogue to establish acceptable norms of behavior in cyberspace.

We have worked hard to build a constructive bilateral relationship that allows us to engage forthrightly on priority issues of concern. And the United States and China, the world’s two largest economies, both dependent on the Internet, must lead the way in addressing this problem.

Regional Architecture

This leads to the fourth pillar of our strategy—strengthening regional institutions— which also reflects Asia’s urgent need for economic, diplomatic and security-related rules and understandings.

From the outset, the Obama Administration embarked on a concerted effort to develop and strengthen regional institutions—in other words, building out the architecture of Asia. And the reasons are clear: an effective regional architecture lowers the barriers to collective action on shared challenges. It creates dialogues and structures that encourage cooperation, maintain stability, resolve disputes through diplomacy and help ensure that countries can rise peacefully.

There is no underestimating the strategic significance of this region. The ten ASEAN countries, stretching across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, have a population of well over 600 million. Impressive growth rates in countries like Thailand – and a 25-percent increase in international investment in 2011—suggest that ASEAN nations are only going to become more important, politically and economically.

Since taking office, the Obama Administration has signed ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation and appointed the first resident U.S. Ambassador to ASEAN. As I said, the President has traveled every year to meet with ASEAN’s leaders– and will continue to do so going forward. The President also has made a decision to participate at the Head of State level every year at the East Asia Summit, consistent with the United States’ goal to elevate the EAS as the premier forum for dealing with political and security issues in Asia.

Looking ahead, it is clear that territorial disputes in the resource-rich South and East China Seas will test the region’s political and security architecture. These tensions challenge the peaceful underpinnings of Asia’s prosperity and they have already done damage to the global economy. While the United States has no territorial claims there, and does not take a position on the claims of others, the United States is firmly opposed to coercion or the use of force to advance territorial claims. Only peaceful, collaborative and diplomatic efforts, consistent with international law, can bring about lasting solutions that will serve the interests of all claimants and all countries in this vital region. That includes China, whose growing place in the global economy comes with an increasing need for the public goods of maritime security and unimpeded lawful commerce, just as Chinese businessmen and women will depend on the public good of an open, secure Internet.

Economic Architecture

Finally, the United States will continue to pursue the fifth element of our strategy: building an economic architecture that allows the people of the Asia-Pacific –including the American people–to reap the rewards of greater trade and growth. It is our view –and I believe history demonstrates – that the economic order that will deliver the next phase of broad-based growth that the region needs is one that rests on economies that are open and transparent, and trade and investment that are free, fair and environmentally sustainable. U.S. economic vitality also depends on tapping into new markets and customers beyond our borders, especially in the fastest-growing regions.

And so President Obama has worked with the region’s leaders to support growth-oriented, job-creating policies such as the U.S.- Korea Free Trade Agreement. The Administration has also worked through APEC and bilaterally to lower economic barriers at and within borders, increase and protect investment, expand trade in key areas, and protect intellectual property.

The centerpiece of our economic rebalancing is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—a high-standard agreement the United States is crafting with Asia-Pacific economies from Chile and Peru to New Zealand and Singapore. The TPP is built on its members’ shared commitment to high standards, eliminating market access barriers to goods and services, addressing new, 21st century trade issues and respect for a rules-based economic framework. We always envisioned the TPP as a growing platform for regional economic integration. Now, we are realizing that vision—growing the number of TPP partners from seven when President Obama took office to four more: Vietnam, Malaysia, Canada and Mexico. Together, these eleven countries represent an annual trading relationship of $1.4 trillion. The growing TPP is already a major step toward APEC’s vision of a region-wide Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific.

The TPP is also attractive because it is ambitious but achievable. We can get this done. In fact, the United States is working hard with the other parties to complete negotiations by the end of 2013. Let me add that the TPP is intended to be an open platform for additional countries to join – provided they are willing and able to meet the TPP’s high standards

The TPP is part of a global economic agenda that includes the new agreement we are pursuing with Europe—the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Transatlantic trade is nearly one trillion dollars each year, with $3.7 trillion in investments. Even small improvements can yield substantial benefits for our people. Taken together, these two agreements—from the Atlantic to the Pacific—and our existing Free Trade Agreements, around the world could account for over sixty percent of world trade. But our goals are strategic as well as economic. Many have argued that economic strength is the currency of power in the twenty-first century. And across the Atlantic and Pacific, the United States will aim to build a network of economic partnerships as strong as our diplomatic and security alliances—all while strengthening the multilateral trading system. The TPP is also an absolute statement of U.S. strategic commitment to be in the Asia-Pacific for the long haul. And the growth arising from a U.S.-Europe agreement will help underwrite NATO, the most powerful alliance in history.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I believe President Obama’s strategic focus on the Asia-Pacific is already a signature achievement. But its full impact will require sustained commitment over the coming years.

I would leave you with a simple thought experiment that says a great deal about the role of the United States in shaping the way forward. I think it’s fair to ask: without the stabilizing presence of U.S. engagement over the past seventy years, where would the Asia-Pacific be today?

Without the U.S. guarantee of security and stability, would militarism have given way to peace in Northeast Asia? Would safe sea lanes have fueled Pacific commerce? Would South Korea have risen from aid recipient to trading powerhouse? And would small nations be protected from domination by bigger neighbors? I think the answer is obvious.

Credit for the Asia-Pacific’s extraordinary progress in recent decades rightly belongs to the region’s hardworking and talented people. At the same time, it is fair to say – and many leaders and people across the region would agree—the United States provided a critical foundation for Asia’s rise.

As such, the United States will continue to work to ensure that the Asia-Pacific grows into a place where the rise of new powers occurs peacefully; where the freedom to access the sea, air, space, and cyberspace empowers vibrant commerce; where multinational forums help promote shared interests; and where the universal rights of citizens, no matter where they live, are upheld.

The Obama Administration has worked to make our rebalance to the Asia-Pacific a reality because the region’s success in the century ahead –and the United States’ security and prosperity in the 21st century—still depend on the presence and engagement of the United States in Asia. We are a resident Pacific power, resilient and indispensable. And in President Obama’s second term, this vital, dynamic region will continue to be a strategic priority. Thank you.

<도닐론 연설에 관한 중국 보도>

www.XINHUANET.com 2013年03月13日 08:54:48 来源: 新华社

主持人:美国总统国家安全事务助理托马斯·多尼隆当地时间11日在纽约亚洲协会发表了一场“关于美国现阶段亚太政策”的演讲,其中谈到了美国对朝政策、中美关系发展等问题。来看报道。

(小标题)美要求朝弃核 愿提供经济援助

解说:在谈到对朝政策时,多尼隆表示,虽然美国反对朝鲜研发核武器,但会给予朝鲜经济援助。

同期:美国总统国家安全事务助理 托马斯·多尼隆

60年来,美国致力于维护朝鲜半岛的和平与稳定。这就是说,我们要使朝鲜放弃武力,我们要保护我们的盟友,并使朝鲜半岛实现无核化。美国不会接受朝鲜拥有核武器,也不会对朝鲜研发核武器并有可能针对美国的问题坐视不理。

解说:多尼隆称,美国会坚决保护其盟友韩国和日本的安全。他强调,美国总统奥巴马希望能够和平解决朝鲜半岛问题。

同期:美国总统国家安全事务助理 托马斯·多尼隆

美国会继续敦促朝鲜合理解决问题。奥巴马总统已多次强调,他就任期间愿意向那些肯松开拳头的人伸出友谊之手。美国随时准备着帮助朝鲜发展经济,帮助朝鲜人民改善生活,但前提是现在的朝鲜必须做出改变。

(小标题)美欢迎中国和平崛起

解说:在谈到对华政策时,多尼隆表示,中美关系对于奥巴马第二个任期内的亚太“再平衡”战略具有重要意义,美国欢迎中国和平崛起。他指出,两国关系已经迈入了一个新阶段。

同期:美国总统国家安全事务助理 托马斯·多尼隆

中国领导人的顺利交接和美国总统奥巴马的连任将会为美中关系发展开启新阶段,带来新机遇。

解说:多尼隆强调,发展更具建设性的对华关系将是奥巴马第二任期内的主要任务之一,两国将会共同解决摆在面前的外交、经济与环境挑战。

同期:美国总统国家安全事务助理 托马斯·多尼隆

奥巴马总统多次重申,美国欢迎一个和平、繁荣崛起的中国。我们不愿大家以竞争和对抗的思维定义我们之间的关系。

解说:此外,多尼隆还在演讲中谈到了作为美国重返亚太的重要战略“跨太平洋战略经济伙伴协定”。他表示,该协定作为促进国际贸易的平台欢迎各国加入。他还说,奥巴马政府将会进一步推动亚太地区贸易自由化。

新华社记者穆序尧、长远,报道员克丽丝廷·席弗纳纽约报道。(完)

2. 인민망/2013.3.13

2013-03-13 09:40 人民网

<중략>

专业人士看好中国

3月11日,“两会”进入尾声,人民网记者出席了美国总统国家安全事务助理多尼隆(Tom Donilon)在亚洲协会地下礼堂举行的有关亚太政策的演讲,他其中阐述了美对华政策主张,表示美方欢迎一个和平、繁荣的中国崛起,拒绝“大国冲突论”,将继续高度重视中美关系,进一步同中方加强沟通,推进合作、管控分歧,共同致力于构建中美新型大国关系等。随后,人民网记者在采访中感到,美国一些主流人士也高度评价中国发展世界的贡献。

3. 인민망 군사/2013.3.13/

中美关系正处在继往开来的重要阶段 反对将网络空间变为新的战场 希望朝核各方坚持对话协商

2013年03月13日06:33来源:解放军报

据新华社北京3月12日电 (记者杨依军、许栋诚)外交部发言人华春莹12日说,美国总统国家安全事务助理多尼隆11日在美国纽约亚洲协会发表了关于美亚太政策的演讲,中方对其演讲中的积极表态表示欢迎。

华春莹介绍说,多尼隆在演讲中表示,美方欢迎一个和平、繁荣的中国崛起,拒绝“大国冲突论”,将继续高度重视中美关系,进一步同中方加强沟通,推进合作、管控分歧,共同致力于构建中美新型大国关系等。

“当前,中美关系正处在继往开来的重要阶段。”华春莹说,“中方希望与美方一道,继续按照两国元首达成的重要共识,共同探索构建一条以尊重为前提、以合作为途径、以共赢为目标的新型大国关系之路。”

据新华社北京3月12日电 (记者杨依军、熊争艳)外交部发言人华春莹12日表示,中方反对将网络空间变为新的战场。

11日,美国总统国家安全事务助理多尼隆在美国纽约亚洲协会就美亚太政策发表演讲时,就网络安全问题表达了关切。华春莹在例行记者会上就此回答了记者提问。

华春莹指出,中国政府高度重视互联网安全问题,坚决反对并依法打击网络攻击行为。网络空间需要的不是战争,而是规则与合作。

“中方一贯主张国际社会应致力于建设一个‘和平、安全、开放、合作’的网络空间,反对将网络空间变为新的战场。希望各方采取建设性和合作态度共同维护网络空间的和平与安全。”她说。

据新华社北京3月12日电 (记者杨依军、熊争艳)外交部发言人华春莹12日就对朝鲜制裁表示,制裁本身不是目的,希望各方坚持对话协商。

当日例行记者会上,华春莹说,联合国安理会第2094号决议已经明确表明了国际社会反对朝鲜核试验的立场,同时承诺通过对话与谈判的和平方式解决朝鲜半岛核问题。

“中方始终认为制裁本身不是目的。”她说,“我们希望有关各方能够继续坚持对话协商,致力于在六方会谈的框架下解决朝鲜半岛核问题,并探讨实现半岛和东北亚地区长治久安的有效途径。”

(来源:解放军报)

4. 양지에츠 외교부장 발언/2013/03/09

(미중관계)

路透社记者:中国已产生新一届领导集体,美国奥巴马政府也开始了第二任期,现在美国内对中美关系何去何从有各种议论。请问您认为中美关系今后将如何发展?美国在亚太推行“再平衡”战略。您认为中美应如何处理好在亚太的互动?

杨洁篪:近年来,在中美双方共同努力下,两国关系总体保持稳定发展势头。

胡锦涛主席与奥巴马总统成功互访并先后12次见面,习近平总书记在奥巴马总统连任后与其互致信函。两国领导人就中美共同建设相互尊重、互利共赢的合作伙伴关系,探索构建新型大国关系达成重要共识。两国对话磋商机制日臻完善,各领域交流合作取得重要成果。

时代在发展,我们应当超越意识形态的不同,摒弃陈旧过时的观念,切实尊重和照顾彼此核心利益和重大关切。美方尤其应妥善处理台湾等敏感问题。我们希望美方与中方一道,致力于构建中美新型大国关系。这种新型大国关系应该以尊重为前提、以合作为途径、以共赢为目标。这不仅是世界和平与发展的大势使然,也是中美各界人士和国际社会的共同期盼。

40多年前,两国老一辈领导人高瞻远瞩,在极其困难的条件下重新打开了中美关系的大门。在21世纪的今天,在世界面临众多问题和挑战的背景下,中美双方更要有大智大勇,更要善于求同存异,从而筑就一条前无古人、后启来者的新型大国关系之路。

亚太是中美利益交织最密集、互动最频繁的地区。中方欢迎美国在亚太地区发挥建设性作用,同时美方也应尊重中方的利益和关切。亚太事务应该由地区国家商量着办。我们希望美方同中方一道,努力增进两国在亚太地区的对话合作,携手促进亚太的和平、稳定与繁荣。

(중일관계)

日本《朝日新闻》记者:中日在钓鱼岛问题上对峙已经持续半年之久,两国关系至今没有改善。两国有没有可能协商制定一些规则,避免两国船只和飞机在钓鱼岛海域对峙等突发事件发生?为改善两国关系,有没有更好的解决办法?

杨洁篪:钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿自古以来就是中国领土。钓鱼岛问题的根源是日本对中国领土的非法窃取和占据。目前的局面是日方一手造成的。日方的所作所为严重侵犯中国领土主权,是对二战胜利成果和战后国际秩序的挑战,严重损害中日关系,也损害了本地区的稳定。

中方采取的坚定措施,显示了中国政府和人民维护国家领土主权的坚强意志和决心。日方应正视现实,以实际行动纠正错误,同中方一道,通过对话磋商妥善处理和解决有关问题,防止事态升级失控。

正确认识和对待历史是发展中日关系的重要基础。日本军国主义发动的侵略战争给包括中国在内的亚洲受害国人民带来了深重灾难。事实反复证明,只有尊重历史才能赢得未来;日本只有正视和深刻反省历史,才能搞好同亚洲邻国的关系。

中日发展长期健康稳定的关系符合两国和两国人民的根本利益。中方愿在中日四个政治文件确定的原则和精神基础上继续发展中日战略互惠关系。我们敦促日方为改善中日关系作出实实在在的努力,为本地区的和平、稳定和发展发挥积极、负责任的作用。

(한중관계)

韩联社记者:2月12日,朝鲜进行了第三次核试验,联合国安理会日前通过了有关对朝制裁的决议。在这个形势下,国际社会正关注中国的态度。请问中方是否会在强调半岛无核化的同时采取其他外交政策,进而阻止朝鲜的第四、第五次核试验?

杨洁篪:朝鲜进行第三次核试验,半岛局势再次紧张,这是我们不愿看到的。安理会第2094号决议表明了国际社会反对朝鲜核试验的立场,同时承诺通过对话与谈判的和平方式解决朝鲜半岛核问题,重申支持并呼吁重启六方会谈。

中方始终认为,制裁不是安理会行动的目的,也不是解决有关问题的根本办法。只有标本兼治,通过对话协商全面均衡解决各方关切,才是解决问题的唯一正确途径。妥善处理朝鲜半岛核问题,维护半岛和平稳定,避免半岛生乱生战,符合有关各方共同利益,也是各方肩负的共同责任。

我们呼吁有关各方以大局为重,保持冷静克制,不要再采取导致局势紧张恶化的行动。希望各方多做有利于推动局势缓和的事,坚持接触对话,培育互信,共同寻找实现半岛无核化、实现半岛和东北亚长治久安的办法。中方愿与有关各方及国际社会一道继续为此做出不懈努力。

(주변국 외교 불화문제)

香港卫视记者:近来中国同一些邻国之间的争议问题不时升温。您如何看待中国的周边形势?中国奉行怎样的周边外交政策?

杨洁篪:我小时候喜欢下棋,围棋、象棋都学过,所以从那时候我就知道下棋要胸有大局。看形势,要看大局、看主流、看长远。当前,树欲静而风不止,中国周边环境中复杂因素较前增多了。但综观全局,中国周边形势基本稳定,中国与周边国家关系继续取得进展。

政治上,中国同周边绝大多数国家建立了不同类型的战略伙伴关系,高层互访频繁,去年就达100多起。我想,今后达到200起、300起也不会令人吃惊。邻居要多走动,越走动越亲近。

经贸上,去年,中国与周边国家贸易额达1.2万亿美元,超过中国与欧、美的贸易之和。我搞外交几十年了,以前想都没想到我们同周边国家的贸易额能够达到我们同欧洲、美国贸易的总和,将来可能还要再加上同几个国家的贸易额才能相当于中国和周边国家贸易的总和。同时,在国际金融危机的背景下,中国对亚洲经济增长贡献率超过50%。

人文交流上,去年中国同周边国家人员交流达3500多万人次。亚洲国家在华留学生人数达17万人。中国同多个周边国家成功互办友好年、青年交流等活动。

区域合作上,中国与东盟建成世界上最大的发展中国家自贸区,上海合作组织制定首个中长期发展战略规划,中日韩自贸区谈判、区域全面经济伙伴关系(RCEP)谈判均已正式启动。

关于中国同一些邻国的领土争议,中国维护领土主权和合法权益的决心是坚定的,通过谈判协商妥善解决争议、维护地区和平稳定的意愿也是真诚的。

俗话说,“邻居好,无价宝”。中方将坚持与邻为善、以邻为伴,坚持睦邻惠邻。

亚洲人是聪明的,不比别人差。许多周边国家看得清自己国家、自己地区根本利益之所在,认为同中国的合作很务实,互惠互利。进一步开拓合作,共同营造稳定、繁荣的地区环境是中国和广大周边国家的共同愿望。

下个月将在中国海南举行博鳌亚洲论坛2013年年会,中国领导人将亲自出席年会,届时将有来自亚太地区及其他地区的多位外国元首、政府首脑等领导人、国际组织负责人和各国各界朋友来华与会,会议规格和规模将超过以往历届年会。这将成为一次促进亚洲和世界共同发展的盛会。

Dionysos

2013년 3월 12일 at 9:57 오후

안보보좌관이 말한 대로 되면 우리의 걱정이 좀 줄어들까요?

그런데 저 양반 중국 공산당 총서기 겸 국가수반보다 두 살 어린데도 훨씬 늙어 보이네요.

영문 제목을 보니 백악관 사이트에도 실수가 있는 듯합니다. advisory?

데레사

2013년 3월 13일 at 3:11 오전

미국이 아주 강하게 나오는군요.

과연 약발이 먹힐런지는 모르지만 속으로는 북한도 겁이

좀 나지 않을까요?

나쁜 행동에 보상은 없다라는 말이 가슴에 와 닿습니다.

eight N half

2013년 3월 13일 at 9:53 오전

북한의 나쁜 짓(1953년 정전협정 폐기와 핵 위협)에 상품이나 상금 지급을 거절한다

The United States refuses to reward bad North Korean behaviour.

핵개발 폐지를 위한 협상을 통해서 약속에 따라서 식량과 석유 등의 원조를 했는데

약속을 어기고 핵 실험과 유도탄 발사 실험을 하고 전쟁 위협을 하는데

미국은 약속을 어기고 멋대로 노는 북한과 두 번 다시 똑같은 협상을 하지 않는다

we won’t buy the same horse twice.

앞으로는 핵 보유 국가로 인정도 하지 않을 것이며 멋대로 핵 위협이나

전쟁 도발 시에는 미국의 모든 군사력과 직면하게 될 것이다

warned Pyongyang that it will face "the full range of our capabilities" if it were to carry out its threat of a nuclear attack.

오직 한 가지 사는 방법은 국제 평화와 번영으로의 개방의 문을 열고

핵 개발을 중단할 시에는 버마의 예와 같이 수십억 달라를 원조할 용의가 있고

아니면 더 이상의 6자 회담과 같은 시간 낭비 대화는 없고 이랔과 같이 멸종 뿐이다

But the White House also offered a carrot, with the prospect of substantial economic help if North Korea is serious about abandoning nuclear weapons.

eight N half

2013년 3월 13일 at 10:22 오전

북한에도 미국과 영문에 능통한 인재가 있어서

2013 / 3 /13 자의 선언문을 읽을 수 있으면

쉽게 설명하면 이번에 미군 작전 함정 근처에서

잘못 실수해서라도 알짱거리다가는

조지 워싱톤 항모에서 평양으로 미사일이 날아갑니다

그래도 해결이 안 나면 미국 전체 10척의 항모가 집결합니다

미국 사람은 김 대중같이 말만 하고 책임을 안 지는 게 아니고

한 번 말을 하면 그대로 실천하고 약속을 지키는 게 미국입니다

지해범

2013년 3월 13일 at 11:26 오전

Dionysos님,

advisory는 명사로도 쓰이는 듯 합니다.

지해범

2013년 3월 13일 at 11:28 오전

데레사님,

미 핵잠수함이 동해에 와있는 상황에서 북한이 함부로 도발하긴 어렵겠지요.

문제는 한미군사훈련이 끝난 뒤겠지요.

우리 국방부는 언제쯤 단독으로 나라를 지킬 수 있을지…

지해범

2013년 3월 13일 at 11:30 오전

eight N half님,

의견 감사합니다.